Houses provide shelter, but the best are also expressions of the people who live in them. And while many folks dream of creating a home that’s an expression of themselves, few attempt it. Fewer still manage to hang on to their creative convictions all the way through a long, challenging, hands-on homebuilding campaign. Chuc and Linda Willson are two people who decided to build a house and who’ve made it to the finish line. Their story proves that vision, a frugal building budget and a practical floor plan can come together and create a beautiful, one-of-a-kind home, even for those who’ve never done it before.

Houses provide shelter, but the best are also expressions of the people who live in them. And while many folks dream of creating a home that’s an expression of themselves, few attempt it. Fewer still manage to hang on to their creative convictions all the way through a long, challenging, hands-on homebuilding campaign. Chuc and Linda Willson are two people who decided to build a house and who’ve made it to the finish line. Their story proves that vision, a frugal building budget and a practical floor plan can come together and create a beautiful, one-of-a-kind home, even for those who’ve never done it before.

The Willson’s began building on their 2 acre piece of Manitoulin Island hardwood forest in 2008, while living in a small, older home on the property. Their driving vision was to create a beautiful structure that exists in visual harmony with the landscape, to use ecologically-sound local materials whenever possible, and to incorporate meaningful artistic details in the structure, both indoors and out. In practice, this led to four principles that are both particular to the Willson project, yet universal enough to be repurposed in unique ways in any other custom home driven by the same values.

The Willson’s began building on their 2 acre piece of Manitoulin Island hardwood forest in 2008, while living in a small, older home on the property. Their driving vision was to create a beautiful structure that exists in visual harmony with the landscape, to use ecologically-sound local materials whenever possible, and to incorporate meaningful artistic details in the structure, both indoors and out. In practice, this led to four principles that are both particular to the Willson project, yet universal enough to be repurposed in unique ways in any other custom home driven by the same values.

21st Century Stackwall

The closer to home the better. That’s the Willson’s philosophy when it comes to sourcing building materials, and this naturally led to cedar stackwall construction for most of the above-ground walls. “Manitoulin’s covered in white cedar,” explains Linda, “and it makes sense to use wind-blown cedars and logging waste to make stackwalls”.

Stackwall is an age-old building technique that uses short lengths of round tree trunks set into mortar to create a wall. One log is nestled into the depression created by the two logs below, with round ends sticking out. It’s sort of like stonework, except with wood. And while it’s true that the Willsons found raw, stackwall materials free for the taking on Manitoulin, turning all that potential into walls took lots of effort in two different ways.

“We crosscut all 15,000 cedar stackwall blocks to length for our house using a 12-inch sliding compound mitre saw and a stop block,” explains Chuc. “Sawing took about 4 hours daily for six months, mostly in the winter, working underneath a tarp lean-to.”

“We crosscut all 15,000 cedar stackwall blocks to length for our house using a 12-inch sliding compound mitre saw and a stop block,” explains Chuc. “Sawing took about 4 hours daily for six months, mostly in the winter, working underneath a tarp lean-to.”

Stackwall logs must be debarked before building, but with cedar that’s easy. When cut at the proper time of the year the bark peels readily, or sheds on its own 12 to 18 months after the tree is cut. And since many of the Willsons’ stackwall logs had been down for some time before construction began, much of the bark stripped off easily. That said, the job was still time consuming because there were so many logs to handle. .

Precision block length is always important with any kind of stackwall job, but especially so with the modified approach the Willsons used.

Traditional stackwalls are made with 14- to 20-inch long logs that extend right through from the interior to exterior surfaces. And while the wood involved offers good insulation value, the mortar between that wood doesn’t. That’s why some builders use mortar only along the inside and outside portions of the stackwall, leaving the middle hollow. The Willson’s, however, took another approach.

They built each stackwall in two parts – an inside surface and an outside one, both using 7 inch long logs, with two layers of 1 1/2 inch extruded polystyrene foam between them and some air space. Wire ties every 18 inches extend from one side of the stackwall to the other, binding the two log assemblies together through the foam, creating a total wall thickness of 17 inches. This wall thickness makes for some deep and cozy window sills as well.

They built each stackwall in two parts – an inside surface and an outside one, both using 7 inch long logs, with two layers of 1 1/2 inch extruded polystyrene foam between them and some air space. Wire ties every 18 inches extend from one side of the stackwall to the other, binding the two log assemblies together through the foam, creating a total wall thickness of 17 inches. This wall thickness makes for some deep and cozy window sills as well.

Chuc and Linda worked closely with a small professional building crew throughout the project, not as passive observers , but as hands-on partners. Friends also helped during construction, often giving the building site a festive atmosphere. “How many people still say they love their contractor after the house is done?” asks Linda. “We do.”

A three-man crew of “wood masons” made sawdust-enriched mortar for stackwall blocks as they went up. Since wood is more absorbent than traditional masonry building materials like brick or stone, special care was taken to shade the stackwall, and keep it damp as it rose, reducing the risk of premature drying of the mortar. CBC Radio is a big part of the Willsons’ life and during the project it was announced that the corporation was to experience yet another cutback in funding. As a sign of support, the Willsons incorporated the familiar logo into the stackwall pattern on one exterior wall.

A three-man crew of “wood masons” made sawdust-enriched mortar for stackwall blocks as they went up. Since wood is more absorbent than traditional masonry building materials like brick or stone, special care was taken to shade the stackwall, and keep it damp as it rose, reducing the risk of premature drying of the mortar. CBC Radio is a big part of the Willsons’ life and during the project it was announced that the corporation was to experience yet another cutback in funding. As a sign of support, the Willsons incorporated the familiar logo into the stackwall pattern on one exterior wall.

Carbon-Neutral In-Floor Heating

Since the Willson house is built on a slope, both the stamped concrete floor on the lower level and the wood-framed second floor have walk-out access. The lower level is plumbed for radiant infloor heating, too, though it’s not fired in the usual way.

Environmental convictions mean that Chuc and Linda refuse to heat with any method that generates greenhouse gases. This led them to install a pellet-fired boiler connected to the hydronic floor pipes, after considering many other options. Although burning wood does release carbon dioxide into the air (which is a greenhouse gas), this carbon was already in the biosphere. Wood heating pellets are typically made from sawmill waste, and the carbon they contain is destined to return to the atmosphere one way or the other. Either the biomass gets burned for a useful purpose, or it sits in a pile outside the mill and rots, releasing the same amount of CO2 into the air as if it were burned. This is why pellet heating systems are considered carbon-neutral. Fossil fuels on the other hand (or electricity generated with fossil fuels), admit new carbon into the biosphere, carbon that hasn’t been part of the environmental dynamic for millennia, if ever. Burning fossil fuels causes the overall increase in atmospheric carbon concentrations that’s believed to be at the root of global warming.

Environmental convictions mean that Chuc and Linda refuse to heat with any method that generates greenhouse gases. This led them to install a pellet-fired boiler connected to the hydronic floor pipes, after considering many other options. Although burning wood does release carbon dioxide into the air (which is a greenhouse gas), this carbon was already in the biosphere. Wood heating pellets are typically made from sawmill waste, and the carbon they contain is destined to return to the atmosphere one way or the other. Either the biomass gets burned for a useful purpose, or it sits in a pile outside the mill and rots, releasing the same amount of CO2 into the air as if it were burned. This is why pellet heating systems are considered carbon-neutral. Fossil fuels on the other hand (or electricity generated with fossil fuels), admit new carbon into the biosphere, carbon that hasn’t been part of the environmental dynamic for millennia, if ever. Burning fossil fuels causes the overall increase in atmospheric carbon concentrations that’s believed to be at the root of global warming.

“Warm floors are wonderful,” smiles Linda. “They make you feel much more comfortable at lower room temperatures.” A bag dumped in the hopper of the Willson’s Harman pellet boiler every day or two keeps things warm. The hopper holds enough pellets to burn for two to three days unattended.

Art Is Everywhere

xBesides using ecologically sound building materials and a floor plan suited to their lifestyle, the Willsons incorporated art into many structural areas of their home, and the bottle wall is one example. It’s a four foot circular pattern of coloured glass bottles that extend all the way through a west-facing wall. As the sun travels across the sky, its light passes more and more strongly through the glass, creating a rising display of colour. The Willsons also hired local artists to contribute to the project in other ways.

xBesides using ecologically sound building materials and a floor plan suited to their lifestyle, the Willsons incorporated art into many structural areas of their home, and the bottle wall is one example. It’s a four foot circular pattern of coloured glass bottles that extend all the way through a west-facing wall. As the sun travels across the sky, its light passes more and more strongly through the glass, creating a rising display of colour. The Willsons also hired local artists to contribute to the project in other ways.

David Migwans is an Ojibwa artist who carves wood, stone and antler, works with clay and paints. He spent weeks at the Willson house adding carved details into wooden lintels, door and window trim using hand tools and his uniquely Native artistic vision.

David Migwans is an Ojibwa artist who carves wood, stone and antler, works with clay and paints. He spent weeks at the Willson house adding carved details into wooden lintels, door and window trim using hand tools and his uniquely Native artistic vision.

Gerald Gerard, another woodcarver and friend, created carvings on corner posts. Carvings of animals heads representing the four directions of the Native spiritual tradition along with a stylized sun adorn a representation of the Native medicine wheel on an exterior wall.

A love for the land, a willingness to live out meaningful environmental convictions, and a commitment to hard work, learning and making a house a home. These are the virtues the Willson’s brought to their homebuilding adventure. What would the world look like if more people were this brave?

Special Places

Chuc and Linda sell vegetables and preserves from their organic garden. They also grow much of their own food, and this means they have good use for a large food prep area, a design feature that’s part of the floor plan in a big way.

Chuc and Linda sell vegetables and preserves from their organic garden. They also grow much of their own food, and this means they have good use for a large food prep area, a design feature that’s part of the floor plan in a big way.

“I’ve always wanted a summer kitchen,” admits Chuc, “and now I have one.” It’s an unheated area at the back of the house that’s designed to be cool during hot months, when produce is being prepped for sale or preserves are made. Most of the summer kitchen wall area is part of the masonry foundation that holds back sloped soil, so it’s naturally cool. The floor plan also includes a regular kitchen for day-to-day use, and a root cellar cast as part of the 17”-thick poured concrete foundation wall.

“I’ve always wanted a summer kitchen,” admits Chuc, “and now I have one.” It’s an unheated area at the back of the house that’s designed to be cool during hot months, when produce is being prepped for sale or preserves are made. Most of the summer kitchen wall area is part of the masonry foundation that holds back sloped soil, so it’s naturally cool. The floor plan also includes a regular kitchen for day-to-day use, and a root cellar cast as part of the 17”-thick poured concrete foundation wall.

The 24 by 32 foot second level of the house is essentially one big bedroom, with a small, separate sunroom and bathroom. Big south-facing windows in the sunroom and bedroom zone give the space a light, airy open feeling. It’s a great place to be. The Willsons are preserving a small part of the old house as guest accommodations.

A Different Way to Build

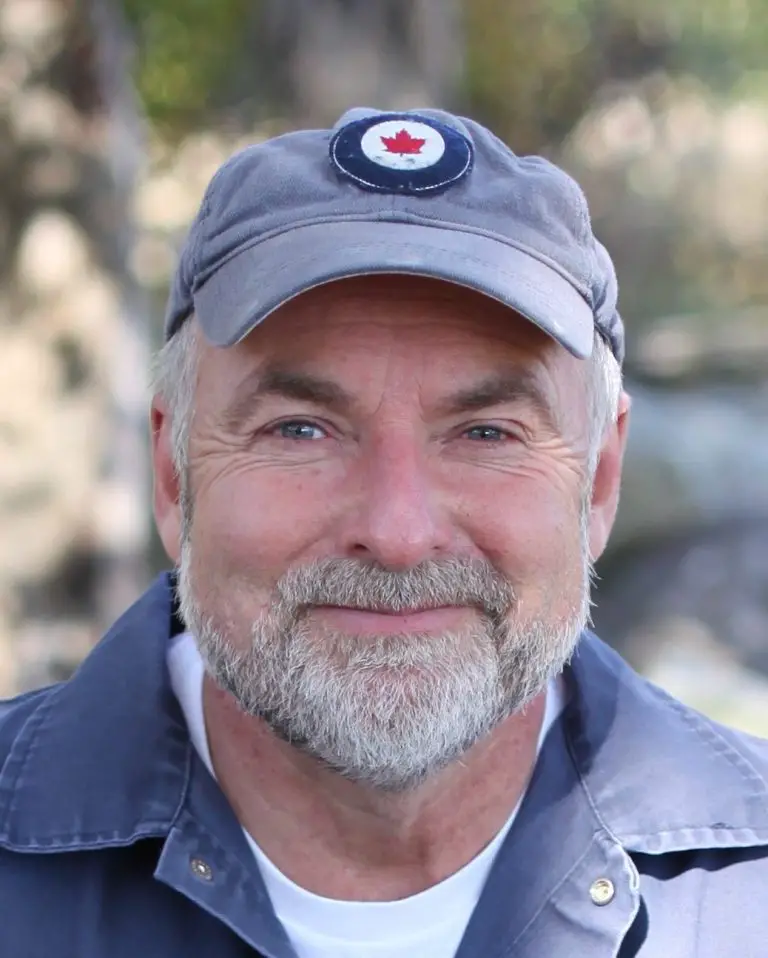

“Neither Chuc nor I are experienced builders,” explains Linda, “but when you want to do something badly enough, you’ll figure out a way.” Both Linda and Chuc are in their sixties, and despite Linda’s health challenges, they jumped into this ambitious project with both feet. “We couldn’t have completed the work without our contractor, Peter Gordon and his crew – Todd Gordon, and Jim Monroe (in his late 70’s). Other local contractors were essential, too”, says Chuc. In practice the Willsons wore many hats: planners, architects, labourers and clients all rolled into one, complimenting the contribution of hired professionals and friends where ever skills, energy and time allowed. “This certainly isn’t the usual way to build a house,” explains Linda, “but the creative involvement is something more people should experience. We’d do it all over again.”