- Reading time = 7 minutes

If you’ve ever loved a place for a time, then had it slip out of your life, I’ve got a story to tell, and some thoughts to share.

My Original Special Place

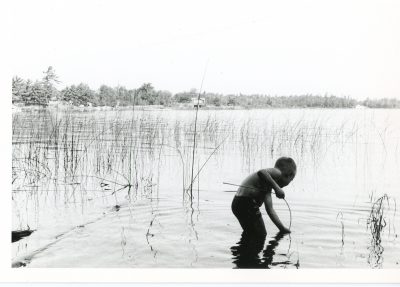

Sometimes little things make big differences, especially when those little things happen when you’re young. The main reason I live on Manitoulin Island, Canada, work with wood, stone and soil, and love my rural life is because of great childhood experiences I had at our lakeside family cottage near Pointe-au-Baril, Ontario, Canada, 3 hours drive from the city home where I grew up. I remember the moment when I was 12 years old, as the waning days of summer brought their usual back-to-school anxiety, that I wondered how I could live near water, trees, big skies and generous soil full-time. My life ever since has been a quest to find and live that life. In the photo above I’m 7 years old, doing what I did most summers growing up at the cottage.

But the big choices I made to follow my dreams of rural living, beginning in 1985, meant that the cottage — a very humble family heirloom since 1926 — stopped being part of my life. That said, it’s still very much part of who I am, and that’s the problem.

The summers I spent in Pointe-au-Baril as a boy led me to a wonderful relationship with my grandfather, to an appreciation of nature, a love of the smell of white pine trees, early experiences learning the joys of manual labour, and the urge to make a living for myself where pavement is a rare thing. And in a strange way, the cottage also led me away from itself. It’s kind of like a parent that way. Good parents work themselves out of a job. And in the case of the cottage, there’s someone that came before me, and that someone has an unusual history.

The Roots of Personal History

Our Pointe-au-Baril cottage gave me the temperament to live a rural life on Manitoulin Island — a more practical place than the cottage to raise kids in the countryside and to live year-round and to grow things. So I got everything that I needed from cottage life here on Manitoulin and more. That’s why the practical side of my brain eventually had to admit that there was no need to drive 5 hours to swim and fish when I could enjoy the same thing 10 minutes walk from my house. Logical, yes, but my heart still isn’t completely convinced that my family and I did the right thing in selling.

In many ways my heart still sits inside a boy casting for sunfish on the shores of Pointe-au-Baril, though it’s been a couple of decades since I’ve seen the place. No matter how hard you try to think of properties as investments, objects of prestige, or just plain shelter, doesn’t the emotional side eventually worm its way in? Homes and cottages are places where attachments grow and persist, often way beyond what makes sense. At least that’s the way with me.

Cottages Live Forever, But Not So Little Boys

In the summer of 1988 — the first summer in 18 years that I didn’t visit the cottage — a 50-year drought gripped all of North America. Do you remember it? Eight weeks without a drop of rain where we live. It even killed a few full-grown trees at the cottage, including a gnarled and quite rare apple tree that grew wild out of a rock crack just a few feet from the water’s edge, along the almost-soil-free shoreline of the Canadian Shield. It was a brave tree, and tough. It had probably sprouted from an apple core that washed ashore decades earlier, and it was the only apple tree I’ve ever seen growing wild in cottage country. I’d enjoyed fruit from that tree for years, and even though it would have been easy to keep it alive with buckets of lake water just a few feet away, I was somewhere else at the time, building a new dream. I didn’t even know the tree needed me.

When I heard that the apple tree had died, I felt like Jacky Paper in Puff’s sad dragon song. Worse, actually. Cottages live forever, but not so little boys. This was the moment that I first realized how I was growing away from what had been my very favourite place in the world (and still is, in my heart). You’d think I could have seen it coming, but I didn’t. We’re often not as smart as we think we are.

Sometimes it takes a while to come to terms with change. My family and I spent 8 years deciding to sell the cottage, weighing the practical fact that it was hardly used against the good memories that still lived there. And when the decision to sell was made final in 1996, I came to understand something that made the task easier.

Saying Farewell – A New Dream Awaits

I now see how issues like these go beyond practicality. They’re also about making room for others to enjoy a place and to build a relationship with it. What right do I have to hang on to a jewel, just to keep it buried? Somewhere out there was a family — with young children and grand kids as it turned out — whose lives are now enriched by an attachment to the rocky shoreline, the big white pine trees and the fishing point that still means so much to me. The last thing we did for the cottage was to hand it over to the very best kind of new owners, along with some of the old stories to help them grow new roots where our old ones left off. It was the least I could do for the place.

My last experience at the cottage was strange. I was driving through the area, so I turned off the highway and drove the 5 miles in to see the place and to say hello to the new owners. The door was open, and the place was lived in, but no one was home. Perhaps they were out on a boat for a day of fishing. I took a swim from my favourite point, breathed the delicious aroma of a healthy lake, then lay on my favourite granite rock in the sun, basking like one of the big turtles I was never quite able to catch as a boy. A couple of hours went by with no owners around, so I snuck inside. The place was neat, it was filled with other people’s summer stuff, but I could tell it was loved. I walked out, and climbed into my truck with that one last memory.

Is Loving Worth It?

Have you ever tried convincing yourself that good memories aren’t worth the cost? That you’d be better off without ever loving anything, and in that way never finding you have to say goodbye? It’s tempting sometimes, but not worth it. Not even close. Bidding fond goodbyes is inevitable in this broken and fallen world we find ourselves in, and the fact that I’m now 60 years old reminds me of that fact. But I can’t complain. All the bitter-sweet things in my heart just mean that I’ve loved something enough to wish it could go on forever. I’ve experienced something that’s good enough to enter into my personal, good-old-days hall of fame. And I don’t suppose life gets much better than that on this side of eternity, does it?

Do you have a favourite place in your heart? Is it still part of your life? A memory only? Let me know what you think at [email protected]

I hope you found this article interesting. Please consider helping me cover the cost of writing and publishing content like this. Click the “buy me a coffee” button below for a fast, safe and simple way to make a contribution. Thank you very much!

– Steve Maxwell