- Video#1 Watch Time = 12 minutes

In a world where power tools rule, hand planes still offer the chance to boost the quality of your woodworking in ways you might not realize. This article will show how planes are used in a few different situations, including some you may never has seen before. No matter how good power tools get, there will always be jobs where a well-tuned hand plane is the best woodworking option. Drum-tight joints in stain-grade trim, hand-beveled raised panel doors, or hand-planed solid wood cabinet parts and fireplace mantles – in cases like these you can’t do better than a razor-sharp hand plane. And if this wasn’t enough, hand planes are undergoing something of a renaissance these days with the appearance of new planes on the market. More on this later.

Before I share with you what I’ve learned about hand planes over the last 40 years, watch the video above if you haven’t. It shows how I use a hand plane to smoothen rough-cut lumber with no loud noise or airborne dust. You probably haven’t seen anything like this before. I don’t always smoothen wood this way any more, but I did this exclusively for years making custom furniture for clients as a teenager. I don’t know anyone else who planes lumber by hand like this in the old fashioned way, but it’s fun, effective, quiet and dust-free.

How to Choose a Hand Plane

Build a collection of a few good planes, learn to keep them sharp and they’ll improve your woodworking results forever. As long as the world still has electrical outlets that work, hand planes will never replace power tools completely. That’s fine because a good hand plane can still supplement electric tools in ways that make your work stand out. The thing is, it’s easy to waste your time with a bad hand plane, too. Cheap, modern planes are junk, though there are ways to avoid the bad-plane pitfall.

If you’re new to planes, consider starting with one of the smaller models. At just under 10″ long, a #4 smoothing plane is a good size. Plan to spend at least $150 to $200 on a good smoothing plane because anything cheaper will probably cause you frustration. I have never seen a decent hand plane for sale in hardware stores any more (they’re made too cheaply), so I wouldn’t hold out much hope there. Planes built before WWII are almost universally good, but it’s not always easy to tell how good an older plane is at a garage sale or second-hand store. Some of the best new hand planes in the world come from Canada. Beginning several months ago I tried the new line of Busy Bee planes and they offer the best combination of high quality and reasonable price that I’ve seen. You can see these tools in action in the video below:

- Video#2 Watch Time = 13 minutes

Before you write all this hand plane stuff off as the wishful thinking of a guy trapped in a time warp, think again. More than once, a few swipes with a well-tuned hand plan have made all the difference in my work, even on the modern, fast-paced jobsites and cabinet shops I’ve worked in during the past. And it’s not just about installing better trim, either.

Hand Planed Raised Panels

In a world where so many factory-made frame and panel cabinet and vanity doors all look like they came rolling off the same conveyor belt, a hand plane offers a quiet and simple alternative. And it all comes down to beveling the edges of raised panels by hand, instead of the usual router table or shaper-cut profiles. Sounds slow and labour-intensive, I know, but it isn’t really. It’s actually fun and surprisingly efficient. You can see the process unfold on video below.

- Video#3 Watch Time = 8 minutes

All frame and panel designs offer two things. First, they look terrific because of the texture and visual variety they present. That’s what you can see in the photo below. But frame and panel designs also limit the troublesome seasonal movement that’s the hallmark of all wide expanses of solid wood. The inner panel gets larger and smaller with changes in humidity, while the outer frame remains more or less the same size. Building your own hand-beveled frame and panel doors does all this in a format that looks way more classic than anything available off the shelf.

Frame and panel work always begins with the horizontal and vertical members of the door frame. These are called stiles (vertical) and rails (horizontal). You can use biscuits or dowels to connect these parts. Even pocket screws do just fine if you’re making raised panel wainscoting that’s destined to be installed permanently against a wall.

When it comes time to making your raised panels, there’s a timesaving trick. Your plane doesn’t actually cut most of the bevel. Instead, use a tablesaw to hog off most of the waste with the blade tilted 15º to 20º from plumb. The plane comes into use afterwards for removing the saw marks while making the bevels all a consistent width and thickness. Keep trying one of your grooved frame members periodically on the edges of the panel as you plane. The idea is to adjust the thickness of the bevel’s edge (with your plane) so it plugs nicely into the stile and rail grooves you prepared earlier. To help you get bevel width perfectly consistent, use a combination square and pencil to mark a line some consistent distance in around the perimeter of the panel. A 2-inch wide bevel is ideal for most cabinet doors. Expect to pay $150 to $200 for the kind of smoothing plane that’s ideal for raised panel work. If you didn’t watch the video showing all this farther up on the page, scroll back and watch how it all works.

Hand-Planed Surfaces

If you really want to look like an old-world master, consider using a hand plane for smoothing solid wood cabinet sides or fireplace mantles. That’s right, no sanding just a hand planed surface as a final step. I built the cabinet you see above back in the mid-1980s with hand tools only, including the use of a plane for final smoothing of the rough white pine lumber I was building with. The subtle undulations left behind by a slightly curved blade of the plane is a hallmark of traditional woodwork and much appreciated in a world where too much is accomplished by machine.

Hand planing like this progresses surprisingly quickly, too. It takes less than half an hour to hand plane a rough-cut 4×10 pine mantle that’s eight-feet long. That’s twenty bucks of labour time to create a one-of-a-kind home feature that can easily be sold for several hundred dollars if you wanted to start a little sideline business.

Although you can use a smoothing plane for this kind of surface work, a scrub plane is another option. It has a slightly curved blade that creates subtle and unmistakable undulations in the wood surface. You can get a good scrub plane for about $150.

How to Sharpen a HandPlane

By now I hope you’re eager to give this hand-plane thing a good try because it really is worthwhile. But there’s one more thing you need to know first. A razor-sharp blade is absolutely essential. And I mean razor-sharp, as in sharp enough to shave hair cleanly. That’s how you get paper-thin shavings like the one you see above. Without an ultra-sharp blade nothing happens. The good news is that sharpening needn’t be the pain you probably have experienced it to be. Not if you have the right sharpening equipment, that is.

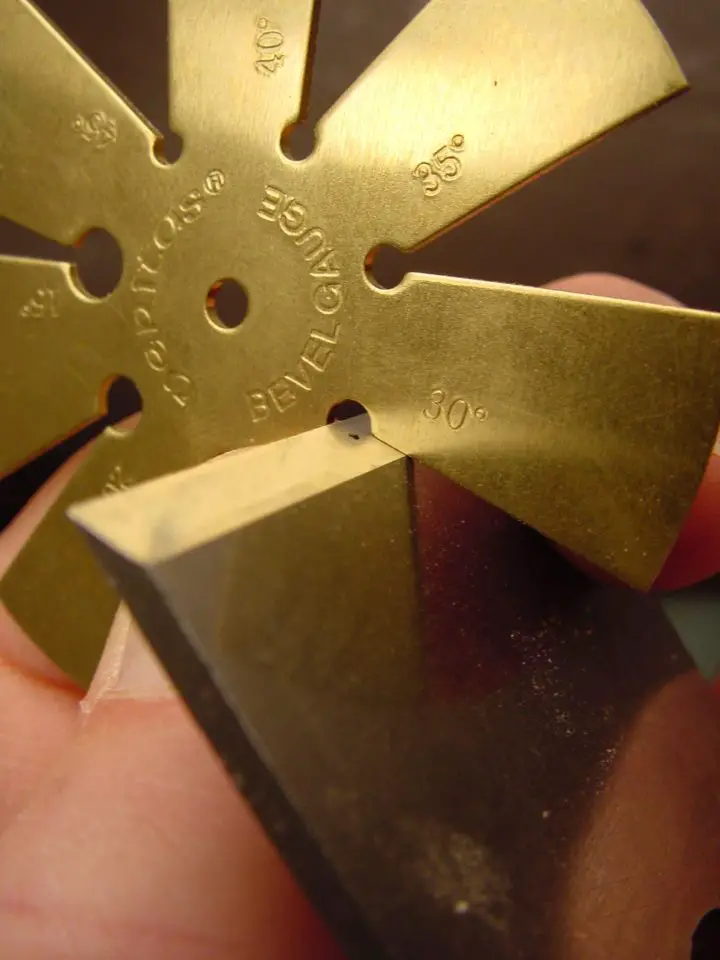

There are two requirements behind every sharp edge: a correct bevel angle of 25 to 30 degrees at the tip of the plane blade, and a finely honed edge that’s capable of cleanly shaving arm hair or slicing curls of end-grain from softwood test blocks. Sharpening a plane iron (or any edge tool) is a product of these two steps: grinding (doesn’t need to happen often) and honing (needs to happen often).

If your plane is brand-new, you can probably skip the first sharpening step altogether – the grinding. Top-quality, factory-fresh planes are always ground correctly. But let’s say you’re dealing with an old plane iron that’s seen lots of brutal action, perhaps even opening paint cans or stripping furniture.

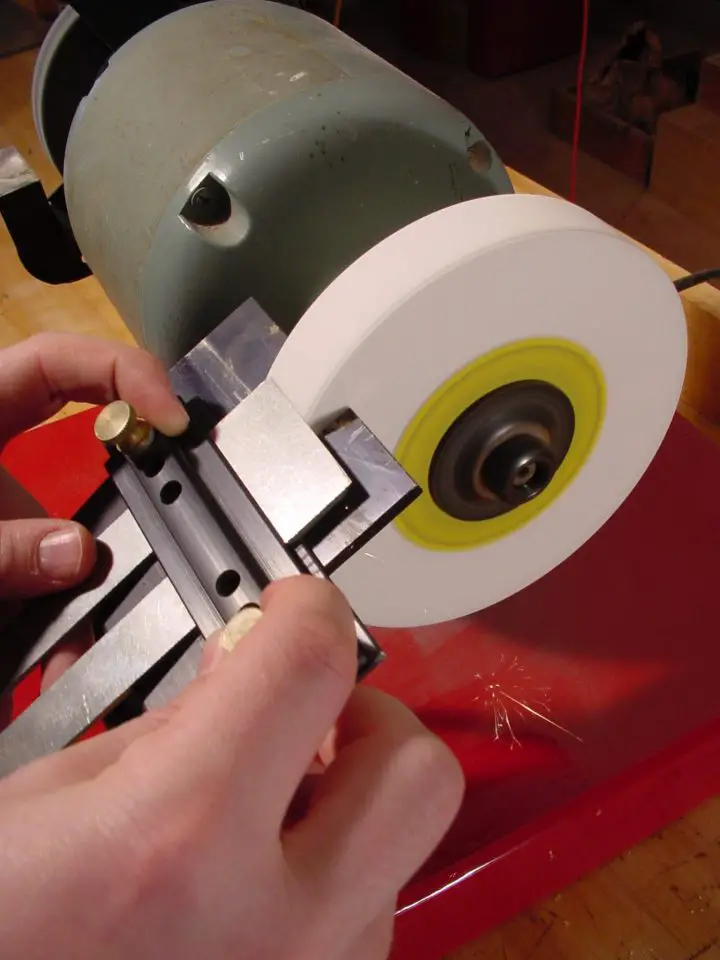

Successfully grinding a plane iron like this demands the same things needed for reworking the business-end of any edge tool. You’ll need a stationary grinder with a tool rest capable of supporting the plane iron securely while reshaping its surface with minimal heat built up. That’s my setup in the photo below. Understand right now that heat is the enemy of every edge tool. If your plane iron becomes yellow or blue at the tip because of grinding heat, it will never hold an edge properly again. At least not until it gets re-tempered by someone expert at working high-carbon steel.

Here’s another thing . . . When it comes to tool grinding machinery, you’ll find more than a few wet grinders that can do a great job for you. Trouble is, they’re usually way more money than what you can justify for occasional tool grinding. And make no mistake, grinding doesn’t have to happen all that often – perhaps only once or twice a year, even with heavy use. The good news is that an ordinary, inexpensive bench grinder can do a great job preparing plane irons, as long as you upgrade the tool rest and the grinding wheel. A generous size, easy bevel angle control, and a sliding tool holder are all features you’ll find on good tool rests.

While you’re thinking about your grinder, you should consider is a cool-running, soft-bond wheel. Except for their white color, these look the same as regular grinding wheels. But the softer consistency means that fresh, sharp abrasive particles are continually being exposed while grinding. These remove tool steel with less friction than the old, rounded particles that develop on traditional wheels. The result is a cooler grind, though the cool wheels do have a somewhat shorter working life because they’re soft.

But even with a cool-grind wheel on your side, you still need to be careful. Don’t make sparks for more than two or three seconds before dipping the tip of the iron in cold water for five seconds. Keep the grinding and cooling process going until the entire bevel shows an even, fresh surface, with a small burr of rough metal formed at the tip.

Honing comes next, but don’t worry. This is the fun part. Although I have an entire collection of Japanese water stones and diamond stones in my shop, I almost never use them because I’ve discovered something much, much faster. Instead of stones, I go directly from the grinder to a hard felt buffing wheel charged with a chromium oxide abrasive compound. All it takes is two minutes to impart a scary-sharp edge on any freshly ground plane iron. And buffing a slightly dull edge back to exquisite sharpness takes even less time. Just hold the edge of the plane iron tangent to the wheel as it spins, with the tip pointing in the same direction as wheel rotation. Buff the back surface first, then the bevel. When the surface shines like a mirror, you’re done. See the results in the video below.

- Video#4 Watch Time = 1 1/2 minutes

Razor Sharp Tools in Minutes – Really!

As I mentioned before, buffing is the only way I hone my tools and it’s been like this for many years. Buffing is much faster than sharpening stones and the results are better, too. Click here to learn more about the buffing system I use. This is the same system I’ve been teaching in classroom workshops at wood shows.