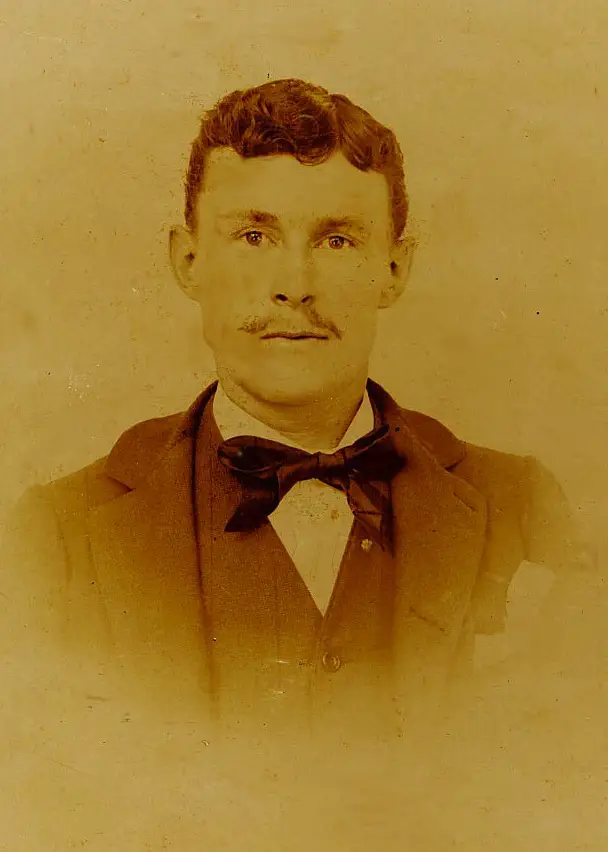

It goes without saying that being a contractor is about making money. Building and renovation is a business. The contractors you hire have families to feed and retirements to hope for, just like the rest of us. But I’ve found that the best contractors leave the world with more than just a quest for profits. They’re also part of a centuries-long history of heroes. That’s why you need to meet a man named Charles Caskey. That’s him above.

Until the fall of 1886, 35 year-old Caskey had only built cottages in the upper peninsula area of Michigan. But that didn’t stop him from bidding on the construction of a 210-room, 625-foot palatial hotel funded by a consortium of railroad and steamship companies as a destination for summer tourists. To make the challenge of this project steeper, the building site was on a small island called Mackinac, 7 miles from the shore of a remote part of the northern Great Lakes. Then there was the building schedule. This new hotel had to be open and ready to accept guests in the summer of 1887, less than a year away. It absolutely had to be done because rooms had already been sold. Clearly, Caskey was no coward.

Caskey closed his cottage-building business for a year, he borrowed huge amounts of money, made timeline promises to wealthy barons like Cornelius Vanderbilt, and assembled a crew of 600 men to live in a tent village set up in the snow and mud of Mackinac Island in March 1887. Similar monster projects around the northeast had depleted the labour supply to the point where Caskey had to pay double wages to get the workforce he needed.

A total of 1.5 million board feet of lumber was sledded across the ice with horses day and night over the winter of 1886/87, until the pile was large enough to see from the mainland. Locals called the project “Caskey’s Folly”. When construction work began in March 1887, three shifts of tradesmen would eventually be pressed into service, working around the clock by lantern and candlelight. But before that even begun to happen, labour unrest flared up. Troublemakers learned about the tight building schedule, so they demanded triple wages. “If we don’t get them, we don’t work and you go down.”

Caskey stood his ground: “Double wages is what we agreed on, and double wages is what you get. And if you don’t like it, you can leave the camp and make your own way back to the mainland. You’re not eating any of my food, you’re not sleeping in any of my tents and you’re not leaving on any of my boats if you quit. The next public boat doesn’t get here for three weeks.” After that bit of head butting, the men got down to what must have been an awesome work pace.

The most amazing part of Caskey as contractor of the Grand Hotel is not just that he pulled off the job with a crew living and working under conditions primitive enough that modern labour inspectors would shut the site down today. It’s not even that all the work happened without electricity, power tools, compressed air or an army of sub-trades ready to swoop in with specialized gear and ready-made components. The truly stunning thing is that the place actually did get done at all. The photo above was taken a few years after the Grand Hotel opened. The photo below shows what it looks like today.

The first rich and privileged Grand Hotel guests stepped off the luxury steam liner that tied up on Mackinac Island, they walked into the lobby of the Grand and checked in on July 10, 1887. Only 93 days earlier the place was nothing more than a mud hole next to a towering pile of white pine lumber. Similar hotels took nearly a year to build at the time. I doubt any of the guests could have realized what an amazing display of stamina was behind the place they’d spend some pleasant, leisurely summer days, but I do. And doesn’t it just make you want to go out and build something great yourself?