This is the fourth chapter of the true story about moving from the city to a rural homestead on Manitoulin Island, Canada 30 years ago. Click here to go back and read Chapter Three

THE BAILEY LINE ROAD CHRONICLES: CHAPTER FOUR – A WELCOME RELIEF

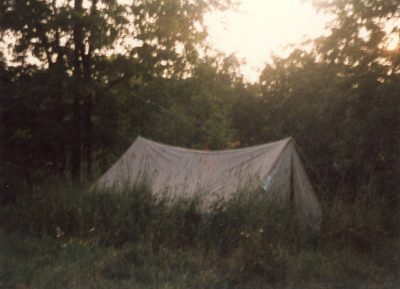

There was no house or buildings on the property when we bought it, and living in a tent with a poplar log propped up over a crack in the limestone bedrock as an open air latrine helped me appreciate the value of a roof over a toilet like never before. The ramifications of a stomach flu one rainy, moonless night helped move the construction of an outhouse to the top of my to-do list. That was a good thing because I’d been working hard wasting a lot of time on projects that either didn’t make sense to do then, or might never make sense to do ever.

“How hard could it be to build an outhouse?”, I thought. “It’s just a small roof and four walls over a toilet seat over a hole in the ground, right?”

The thing is, the outhouse had to be built with virtually no money, and that’s the way it turned out. If you remember it cost me $15 for the load of used cedar planks I bought from Ches Bailey in his field, plus another $20 for new 2x4s for wall frames. It took two bundles of black 3-tab shingles to cover the tiny roof at a cost of $20 for both. Total out-of-pocket expenses for the outhouse was $65 with door hinges and a thumb latch.

Except for a two-story tree house I’d built at the cottage when I was 12, this outhouse would be my first major building project. I’d been given excellent instruction framing houses and wiring in high school during the days when shop class was more than just a babysitting session for students who didn’t make it in the academic stream. But still, I’d never actually designed and built anything on my own before.

My two high school shop teachers were Mr. Piech and Mr. Chin. When it came time to teach us framing, they gave us scale lumber to cut and assemble into walls and roofs, and instructions on all the usual approaches for framing full size buildings. I can’t imagine better shop teachers than these two men. Over the five years I was in their classes they taught me everything from cutting dovetails by hand to wiring a 3-way electrical switch. Everyone in these shop classes learned to tear down a small engine and rebuild it, we got lots of experience welding, cutting and brazing with an oxyacetylene torch, we learned how to do decorative copper enameling by fusing glass to copper sheets in a kiln, and we all knew how to safely use stationary woodworking equipment such as a jointer, planer, bandsaw and tablesaw. No student ever got so much as a scratch in these shop classes, either.

I get mad when I think of the bureaucrats who thought it was smart to dismantle these stellar industrial arts programs during the 1980s, replacing them with weak substitutes that could never deliver the same value. So much potential talent and skills wasted over so many years. As far as I’ve seen these days, all we have are instructors pretending to teach hands-on shop skills and students pretending to learn them.

Although the main shop training I received was in high school, even in elementary school we had decent shop classes. I went to an ordinary public school in an ordinary suburban neighbourhood, but every Friday in grade 8 we were bussed 30 miles to a high school for half-day classes in their teaching shop. I was using a tablesaw on my own by the time I finished elementary school and it makes me both laugh and cry when I see the state of hands-on training in schools these days. Here’s an example . . .

A few years ago a teacher at the elementary school my kids attended in town called me up to ask for help with an exciting new program the school board had launched. This ordinary classroom teacher with no woodworking experience would take kids aside for an hour each week and they’d make small projects in wood.

“It’s a really exciting advance”, she told me. “Do you have any plans we could use to make a bird house? We’re not allowed to use power tools”, she explained. “Oh, and the kids aren’t allowed to use handsaws or electric drills, either. We’ll provide them with ready-made parts and they’ll use small hammers and finishing nails to put projects together. The grade 8 boys are especially excited.”

Really? I guess you’ve got to pity grade 8 boys these days that they get excited over something so lame.

I don’t think my Manitoulin adventure would have gotten off the ground if it wasn’t for the excellent hands-on training I received in high school. It didn’t make me competent in everything, of course, but it did give me the basics and enough experience that I wasn’t afraid to try new tasks. It taught me a little about making things and a lot about learning how to make things.

The thing about building structures in the real world is that there are lots of ways to make mistakes that don’t seem like mistakes until it’s too late. This is especially true when building an outhouse. They may be small, but who builds these things any more? Who knows the little tricks to making an outhouse that works and lasts in the real world?

Back on the ground on Manitoulin Island, Mary and I spent a full day pulling nails out of the old lumber we got from Ches for the outhouse. That sounds like a lot of time to work with a claw hammer and crow bar, but much of this wood was old roof sheathing that have been covered in cedar shingles. There were lots of nails.

By this time in our relationship, Mary and I had been together for 5 years after we met in grade 13. Back then she was the new kid on one side of the math class in high school, with curly hair and a neck scarf. I’d never seen a girl wear a neck scarf before. It was quirky in an attractive way. Mary was different and she came by her difference honestly. She was fresh from Brazil, so a little on the exotic side compared with ordinary Canadian teenage girls. Mary remembers me as the guy who asked a lot of questions from the other side of the room. She says I sounded smart, but I was an academic dud in high school. I understood everything okay during class, but I was too busy building furniture for sale, fixing cars for people in my parents’ garage or living out Bob Seger fantasies on motorcycle road trips with my farming friend Paul. I didn’t study and almost never did homework. Sometimes I wandered into class only to discover that it was the day for some major test that I knew nothing about. I usually bombed tests even when I did know they were coming. That’s why I left high school with a final average of 63% and an official recommendation from the guidance department that I pursue a career as a tugboat captain. Yes, this is for real. That was what the results of my writing of the Jackson Vocational Interest Survey indicated. A few other misfits in my grade also got the tugboat captain recommendation. It must have been a catchall slot for people who didn’t fit elsewhere. Out of a graduating class of about 100 kids, only two other guys got slotted into the tugboat captain stream along with me. Both were my best friends.

One grade 13 class I did particularly poorly in was English. As near as I could tell I should have received a final mark in the high 50s. You needed at least a 70% average to get exempt from final exams for any given class in my school, so there was no question I was writing that exam. A few weeks before the end of the year my English teacher, Miss McKillop, overheard me talking about my auto repair business to a friend and she asked me if I’d take a look at her car. It was a six cylinder GM and the engine was misfiring occasionally on one cylinder. I told her we should begin with a tune up, including new plugs, distributor cap, rotor, plug wires and an air filter.

“That might solve the problem”, I said. “And when was the last time you had the oil changed? Might as well do that, too.” My ability to troubleshoot cars was another spin off from my 5 years of shop class.

Miss McKillop drove over to my parents’ house one evening after supper, I climbed in behind the wheel and we drove to Canadian Tire together. There was definitely a misfire in the engine, but it was intermittent. I ordered parts at the auto counter, she paid for them, then she watched me as I installed everything back at my parents’ place. It felt strange and good to have a woman so interested in watching me do that kind of work. I’d never experienced this sort of thing before and rarely since. Spark plugs, carburetors, cylinder heads and oil changes existed on one side of a dividing line in my life, and women seemed content to stay entirely on the other side. It never occurred to me at the time that my unmarried high school teacher in her early 30s might be interested in more than just a smooth running car. Looking back on it now I wonder.

The tuneup solved the problem, Miss McKillop paid me for my time and left happy. When I got a report card a few days before classes ended, my final mark in English miraculously rose to a nice, round 70%. I guess waiters aren’t the only ones who get tips.

After I’d been watching Mary from a distance across math class for a few months, a motorcycling buddy noticed what was going on. “If you like her, move in now”. His name was Ermis, I’d gotten him interested in motorcycling a couple of years before, and he had some pretty solid relationship advice considering he’d never had a girl friend himself. And as it turned out, Ermis never would have a girl friend, either.

“If you wait too long to make your move, girls start thinking of you as a friend. Once that happens, you’re dead”, explained Ermis. It was strange he should use that term, dead.

I did what Ermis suggested and Mary and I are still together today. Later that summer Ermis died in a motorcycle accident. No one knows exactly what happened, but he was on a long ride with a bunch of other high school biker buddies who’d gotten separated on the road from each other over a half-mile stretch or so. I wasn’t there, but rumour has it that these guys had spent a questionable weekend at some kind of nudist park that went beyond just beach volleyball in the buff. Apparently, there wasn’t as much sleeping going on as there should have been, and as near as anyone can tell Ermis fell asleep at the handlebars and drove into the side of a concrete bridge abutment at 60 mph. The only guy brave enough to ride a motorcycle to Ermis’s funeral was Paul, the high school buddy who got me thinking about a life in the country in the first place. I drove my parents’ 1973 Oldsmobile Custom Cruiser station wagon, the model with the fake wood grain on the sides.

So there I was, pulling nails out of a pile of cedar boards in the middle of nowhere with this particular woman because of romantic advice I took from a guy who never got to have a girl friend himself. Ermis was buried in one of those above-ground mausoleums, with the casket pushed into a compartment that gets covered with a square slab of polished granite. The last thing I remember about the funeral was some guy in overalls walking up next to the priest with a $2 caulking gun in his hand after the last prayer. This workman fumbled to cut the tip on the caulking cartridge with a utility knife, then broke the inner seal with a 4” deck screw while we all stood there in our suits. He laid down a messy bead of white acrylic sealant around the opening before entombing Ermis behind his granite slab. The poorly dispensed white caulking against the dark brown polished stone and the sound of the ratcheting plunger mechanism on the caulking gun seemed such a mundane finale to what had been a very emotional funeral. The last image I have in my mind’s eye of that event is Ermis’s mother standing there, emotionally shell-shocked and hollow, next to an unconcerned maintenance guy in overalls with a brand new, blue caulking gun.

You never really know someone until you spend a full day in the hot sun pulling nails out of boards with them. Reclaiming the lumber we got from Ches was the first all-day manual job Mary and I did together, and it went surprisingly well. Mary maintained a good attitude, especially for someone not used to dirty manual work. As I mentioned before, Mary grew up in Central and South America, moving around with her family as her father got transferred as general manager of different branches of Colgate-Palmolive. She grew up in Trinidad, Costa Rica, Guatemala and Brazil before coming to Canada. In Latin American countries you’re either rich enough to have chauffeurs for every car trip, armed guards by the gate and house maids, or you’re poor enough that you’re thankful to live in a cardboard box. And from what I saw, general managers of Colgate-Palmolive didn’t usually have to opt for the cardboard box lifestyle.

One of the differences between Mary and I stems from the fact that I was raised in middle class Canada and she was raised with maids and a company driver. I’m not sure we’ll live long enough to get over this difference completely, but we’re getting there. I was 25 years old before I set foot on an airliner, while Mary enjoyed numerous month-long seaside vacations in far-flung places with her entire family during childhood. I grew up wearing clothes my mother made or repaired at the kitchen table. Even today, the older clothes get the more I like them. My dad and grandfather used to save nails and bend them back straight during cottage building projects.

Bringing Mary to live in a backwoods corner of the world on a shoestring budget was hard on her parents. Mary’s mom, Rita, is happy with the life her daughter has now, but there was reason for her concern at the beginning. “I cried when I first saw what you had brought Mary to”, Rita told me in September 1990, as we drove back together from the hospital, leaving Mary there after Robert, our first child was born. “Mary was always the one to want to dress up and wear nice clothes. She was my little coquette.” It hasn’t always been easy for Mary, but my hat goes off. She’s done well. I’m also less of a natural born miser than I used to be, and Mary can now enjoy wearing overalls sometimes. I guess iron really does sharpen iron sometimes.

Mary has three sisters, and Rita always required the girls to do housework while growing up, even though live-in maids were in the family home constantly before coming to Canada. This training paid off for Mary (and me) on nail pulling day and beyond. But still, pulling nails from boards in the hot sun demands some getting used to, even if you didn’t grow up with maids. I’d been schlepping lawn mowers since I was 12 and filling barns with square bales of hay and straw for years. I was already hardened to the realities of dirty, manual labour and I’d eventually get hardened more, though hardened isn’t really the right word.

There’s something beautiful but hidden when it comes to working with your hands for long hours in the outdoors. Have you ever experienced it? Simple, tiring, manual work is an acquired taste, but if you’ve got ambition to get something done for yourself (as opposed to just putting in hours for pay), work days grow short. You never seem to get quite enough done during the day, and as the hours slip by you get hungrier and thirstier than you’d normally allow yourself to become. The mounting tiredness is deeper than you’ll experience in regular indoor work, but the internal drive of self-interest keeps you going. This is what happens when ambition combines with a situation where you get 100% of the benefit for your efforts and effectiveness. It’s different than working for hourly pay and it’s quite addictive, at least for me anyway. Sure, Mary and I were only pulling old nails, but it was the first step towards our very own outhouse. Sounds lame? Perhaps, but an outhouse is a huge upgrade when all you’ve had before is a horizontal log latrine.

Have you discovered the beauty of hand labour done with care and pride – even simple hand labour? Mary and I began with an irregular pile of old, bristly wood, and we ended up with neat piles of smooth, orderly lumber organized in stacks according to width. This work was a primitive form of craftsmanship.

We started work at 8am in a June morning on nail day and it was a beautiful evening at about 9pm by the time we’d finished denailing the last boards. Shadows were getting long and we didn’t have the energy to light a campfire and cook. The box of crackers and peanut butter we launched into tasted like a Christmas feast. The canteen of well water filled from Ivan’s kitchen sink was as good as a bottle of excellent wine.

Have you ever noticed how little satisfaction some people feel in life, even though they have more material goods and comforts than a king did a hundred years ago? I think one reason is simply because so few people drive themselves to get tired enough, hungry enough and thirsty enough to truly enjoy simple food and drink. Three thousand years ago a wise man named King Solomon got it right:

“There is nothing better for people than to eat and drink, and to find enjoyment in their work. I also perceived that this ability to find enjoyment comes from God.”

I’m thankful that the universe and human beings are created so real joy can be found in the simple, tiring, dirty jobs of life if we approach them properly. But the proper mindset is key. Looking back, one of the best things about my Manitoulin life is that it gives me the chance to do simple, tiring dirty jobs for myself. Doing these things for money seems to burst the bubble somehow. I love spending all day getting dead tired cutting wood for myself, for instance, but I’m not sure I’d love being a professional woodcutter nearly as much.

Our nail pulling day happened three decades ago and I remember it as golden. Mary remembers it as drudgery, which is actually more impressive. It makes me thankful that she maintained a good attitude even without being fueled by the same satisfaction I felt. Life is so often about attitude, and sometimes this comes down to laughter.

The ability to laugh is one of the most valuable skills of all, especially when that ability extends to laughing at yourself. I was reminded of this when the hole under my outhouse went bad a year after building it. This discovery happened to coincide with a visit from my new neighbour Weldon.

The fact is, holes in the ground seem simple enough, but they’re tricky. The hole under my outhouse performed perfectly that first summer, and this success lulled me into a sense of complacency. Never having lived before with a hole in the ground over the long haul, I didn’t realize the mischief they can get up to.

At this stage in my life my routine involved working on our Manitoulin property each spring, summer and fall, then back to the city to live as cheaply as possible during winter to earn and save money for the next building year. Arriving back on Manitoulin for a fresh season of work in the spring of 1987, the outhouse look tilted. Was it my imagination? No. The clay soil underneath that had been so firm and trustworthy as I dug it the previous summer was now a soupy porridge of collapsed dirt, spring run-off and “substances” of the kind you’d expect to find in any experienced outhouse hole. The soil was collapsing into the unlined crater, and without help the entire outhouse would go down.

The thing about building is that there’s usually no mercy when mistakes are made. There’s no ribbon for participation. If you’ve got trouble, fixes aren’t always easy. My work began by dismantling the seat structure of the outhouse so I could use a shovel to pull out the porridge from the collapsing hole. Distasteful work, yes, but sooner or later shoveling is an expected part of outhouse ownership. What goes in must eventually come out. The question was what to do to stop further collapse of the soil around the hole.

I flirted with the hope that the hole might not get bigger, but that was foolish optimism. It might be fine if the summer was dry, but another winter and the outhouse would fall on its side or worse. The hole was clean now (really, it was), so I worked upside down through the hole in the floor using rocks and mortar to build a circular stone foundation from the ground up to keep the soil at bay. The bottom of the hole was smooth limestone bedrock, so it offered a great foundation for this primitive stonework. The experience was kind of like diving for pearls except in reverse. I’d grab a few rocks and a small bucket of mortar, lower these down into the hole, then dive down with my legs and waist on the wooden floor of the outhouse and the top half of my body below ground level. Ten minutes of working upside down would use up my supply of stone and mortar, then I’d return to the surface for more.

The thing about a young city guy moving to the country is that it attracts the attention of everyone in the area. I was the first person to build anything new on my dead-end road since 1953, so my neighbour Weldon would come around to see what was going on every now and then. His visit this time just happened to coincide with one of my deep dives through the hole in the outhouse floor. I can only guess what went through his mind as he stood there for 10 minutes, watching his new city neighbour with his head and body down in an outhouse hole, legs flailing around up above. One thing’s for sure. Mutual laughter of the kind we experienced when I came up is a great way to make personal connections.

Want to be a key part of making The Bailey Line Road Chronicles a published book? I’m looking for a few good patrons to partner with me to complete this project. Just a couple of dollars a month gets you your own copy of the story when it’s done, and your name on “The Patrons” page.