- Video Watch Time = 9 minutes

Never heard of making your own shop-cut veneer for woodworking projects? Let me show you why it’s a powerful technique that’s worth using because it solves problems and makes woodworking better.

Sometimes the stability and strength of factory-made hardwood veneered sheet goods is perfect for a particular project, except that they don’t make veneered plywood in the species you need. Or maybe you’re leery about using ready-made veneered ply where the veneer is only as thick as a couple of pieces of paper. Perhaps you don’t want to spend $150 on a full sheet of book-matched quartersawn oak plywood when all you really need is one small piece of the stuff. Making your own shop-cut veneered panels is the perfect solution to challenges like these, and once you try it you’ll probably end up using this powerful technique again and again.

Rough-saw solid wood to about 3/8” thick, edge glue these pieces together into thin panels, run the panels through a thickness planer so joints are flat and smooth. Finish up by gluing these panels to a plywood or particleboard substrate. This is the shop-cut veneer process in a nutshell, and even though it sounds simple, there are tricks you need to know to succeed.

Cutting Your Own Veneer

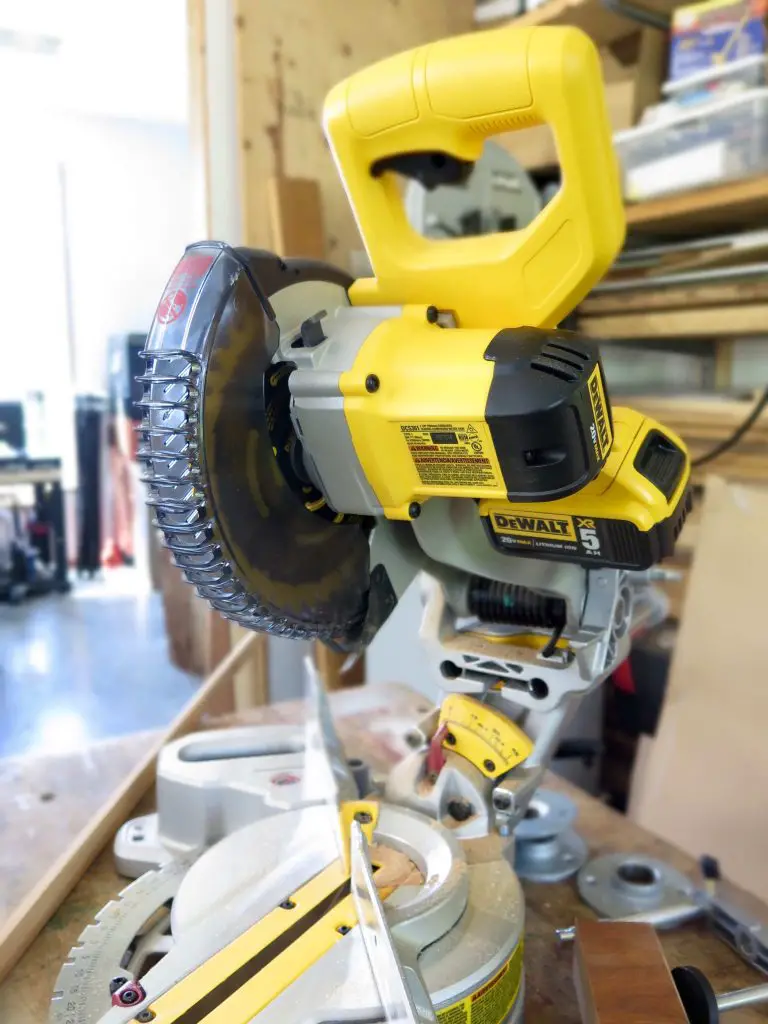

The work begins by resawing lumber to make your own thicker-than-usual veneer stock, but you don’t need a bandsaw to make it happen. I’ve used bandsaws before for jobs like this, but my table saw works well, too. Start by selecting a piece of wood about 1”-thick with an attractive grain pattern. Is your wood rough? Joint one face, then an edge before moving over to your table saw and slice the wood in half on edge. Most of my veneered panels are 6” to 10” wide when complete, so I start with boards that are 3” to 5” wide, sawing each one in half in two passes. Saw along one edge, flip the wood over, then complete the cut from the other edge. Each piece will be approximately 3/8” thick, depending on how wide your tablesaw blade is.

Stunning, book-matched grain patterns – these are one of the best fringe benefits of creating your own veneered panels and now’s the time you’ll see this magic start to appear. Book matching refers to wood grain patterns that fan out in a mirror image along each side of a central glue line. Each board you’re splitting on your tablesaw is a book matched pair, and you’ll get beautiful results if you deal with them carefully.

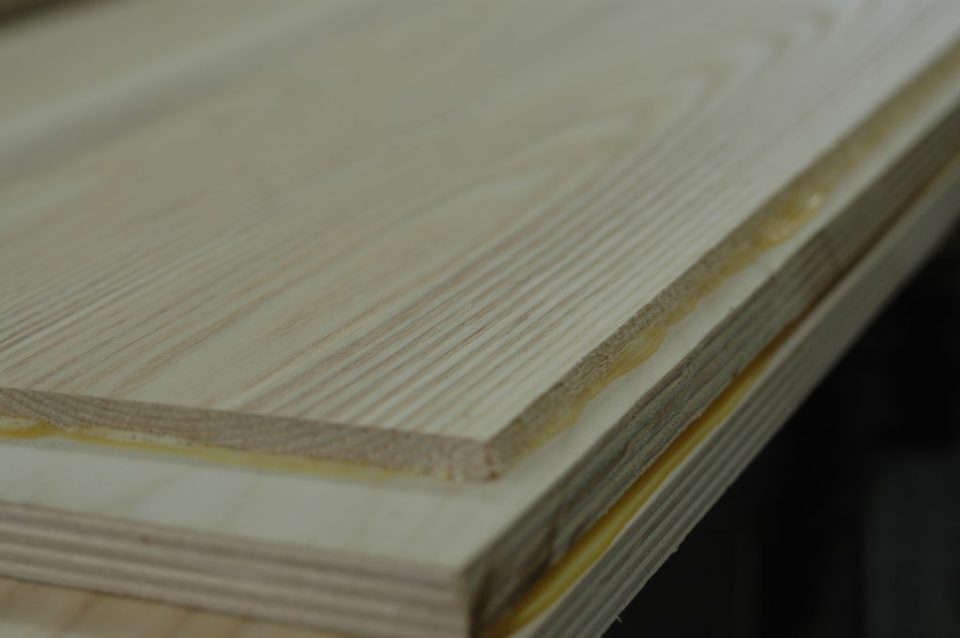

Although you could struggle to apply each piece of shop-cut veneer to your substrate separately, as with conventional, thin veneers, there’s an easier way. Identify the edges of each veneered pair that look best together, joint these edges, then glue the pieces together with clamps, as you would wider panels, making sure the grain elements align perfectly. Remove the wood from clamps when the glue is half hard, scraping off any squeeze out, then run the panels through a thickness planer to even up the joints. It doesn’t really matter precisely how thick the wood turns out to be, though I do find the veneer starts to bend and cup if you plane it thinner than 3/16”.

Gluing Shop-Cut Veneer

My favorite substrate for veneer is 1/2”-thick, cabinet grade plywood, although you could also use particleboard or MDF of the same thickness if you want to save money in exchange for more bothersome dust. Either way, saw your substrate larger than the veneered panels you’ve got (which are themselves larger than the final parts you’re making), then get ready for glue up.

Ordinary carpenters glue is perfect for bonding veneer to a substrate, but you need to spread a lot of it quite evenly over the entire surface. That’s why I prefer to apply glue with a miniature paint roller in jobs like this. Apply a generous coat to the back face of the veneer only. You don’t need to put any glue on the substrate. Next, flip the veneer over, center it on your substrate, then use a pin nailer or tiny hammer-driven brads to stop the veneer from sliding around. One pin in each diagonally opposite corner is all you need. This seemingly small detail is vital for keeping the veneer in place during the clamping phase that comes next. Wood parts tend to slide around when glue is wet, even under clamp pressure. Grab your next piece of veneer and repeat the gluing and stacking process.

Once you’ve got a stack of veneer/substrate pairs, cap the pile with one more piece of substrate (with no glue) to distribute clamping pressure evenly. How many clamps do you have? You’re going to need a lot.

Tighten clamps starting at both sides of one end, working towards the other. There will be squeeze out, but don’t worry. Although it drips down the edges of the substrate stack, it won’t glue them together. Allow this big, tall “club sandwich” to sit undisturbed for a day before removing clamps.

When it comes time to trim panels to final size, be careful to keep the precious centerline of your book matched veneer in the middle after final trimming. Begin by marking the joint line of each veneered panel on the plywood, then use this mark to measure out on both sides to determine where each edge of the veneered panel needs to be sawn to preserve the central joint line.

Master the skills of preparing and applying your own shop-cut veneer, and you’ll gain the ability to make beautiful things with wood and the satisfaction of knowing you can do it. So, as it turns out, not all veneer is second-rate.