Every new home and renovation that’s happened in Canada over the last 40 years was made with lumber cut using carbide saw blades. They’re a universal part of the building scene, yet they’re also under appreciated. This is part of the reason why almost no end users of carbide saw blades know anything about how these things are made. The other part of the reason is intentional obscurity. Tool manufacturers usually keep their industrial processes secret, though not always. Last month I spent most of a day touring one of the world’s newest saw blade manufacturing plants in Udine, Italy. I got special permission to take notes and photos of the event, and the virtual tour you’ll read about here is the result.

Every new home and renovation that’s happened in Canada over the last 40 years was made with lumber cut using carbide saw blades. They’re a universal part of the building scene, yet they’re also under appreciated. This is part of the reason why almost no end users of carbide saw blades know anything about how these things are made. The other part of the reason is intentional obscurity. Tool manufacturers usually keep their industrial processes secret, though not always. Last month I spent most of a day touring one of the world’s newest saw blade manufacturing plants in Udine, Italy. I got special permission to take notes and photos of the event, and the virtual tour you’ll read about here is the result.

The factory was designed and built by international saw blade guru Giorgio Pozzo. He grew up in the family saw blade business back in the 1970s, beginning work on the shop floor when he was only 6 years old. The day I met Giorgio he was wearing a suit that probably cost more than a couple airline tickets to Italy, but there’s more to this guy than just snappy clothes. He’s also amazingly knowledgeable about saw blades. In fact, he designed and built his plant himself, selling it to the international tool company Irwin this past March, staying on as operations manager. The facility is the brightest, whitest, cleanest plant I’ve seen in my life with a vineyard right outside the door. It produces hundreds of thousands of circular saw blades each year, with three shifts of only 10 people each. Here in Canada we’ll see the Irwin Marples saw blades coming from the Udine plant beginning in December. This column gives you an exclusive view of how these blades are made, and how they’ve performed for me in tests.

The factory was designed and built by international saw blade guru Giorgio Pozzo. He grew up in the family saw blade business back in the 1970s, beginning work on the shop floor when he was only 6 years old. The day I met Giorgio he was wearing a suit that probably cost more than a couple airline tickets to Italy, but there’s more to this guy than just snappy clothes. He’s also amazingly knowledgeable about saw blades. In fact, he designed and built his plant himself, selling it to the international tool company Irwin this past March, staying on as operations manager. The facility is the brightest, whitest, cleanest plant I’ve seen in my life with a vineyard right outside the door. It produces hundreds of thousands of circular saw blades each year, with three shifts of only 10 people each. Here in Canada we’ll see the Irwin Marples saw blades coming from the Udine plant beginning in December. This column gives you an exclusive view of how these blades are made, and how they’ve performed for me in tests.

There are distinct steps involved in making any carbide saw blade, and cutting out the circular body is the first. At the Irwin plant this operation happens with a laser. It slices sheets of German-made steel that are fed into the machine. After lasering out the blanks, the disks are heat treated to remove stresses in the metal. Stacks of blanks are sealed in a chamber for hours or days, heated up to 450ºF, then cooled at a controlled rate before moving on to the tensioning process that makes the blade much more resistant to vibration during a cut.

There are distinct steps involved in making any carbide saw blade, and cutting out the circular body is the first. At the Irwin plant this operation happens with a laser. It slices sheets of German-made steel that are fed into the machine. After lasering out the blanks, the disks are heat treated to remove stresses in the metal. Stacks of blanks are sealed in a chamber for hours or days, heated up to 450ºF, then cooled at a controlled rate before moving on to the tensioning process that makes the blade much more resistant to vibration during a cut.

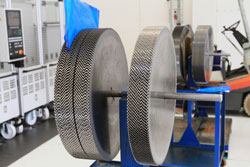

In a plant like this you’d think that all manufacturing would be automated, but there’s one crucial area where hand work and human judgment still matters. Balancing the blades happens when machinists grind each blade body by hand until it’s within specs. Typical 10” saw blades are balanced to within 1 gram across their diameter, while the Irwin blades I saw being made were balanced to within less than 0.5 grams. Each blade is measured for balance individually, then ground on a bench grinder and checked again.

Next step is the carbide teeth. They’re the sharp parts that actually do the cutting, and they’re fastened to the outside of the blade body with an electrical welding process. The carbide teeth are mechanically sorted, aligned and fitted onto the blade automatically, before being ground to shape in the enclosed cabinet of a computer controlled machine.

As interesting as all this is, the bottom line is a blade that cuts well. The 10” general purpose Irwin Marples blades I’ve got in my shop cut everything from 2”-thick hardwood to 1/4” plywood completely smoothly – both faces and edges. Even the bottom side of 3/4” melamine cuts crisp and entirely chip-free. In 30 years of working with wood, I’ve never seen anything like it, though I’m not surprised. The world of tools just keeps getting better, even when you think it can’t any more.