If he were still alive, my Grandfather would turn 118 years old this year, and I want to tell you about him because of what he has to teach anyone who wants to live their life well. Grandpa died in 1995, but the lessons I learned from him still have something to say to me and everyone.

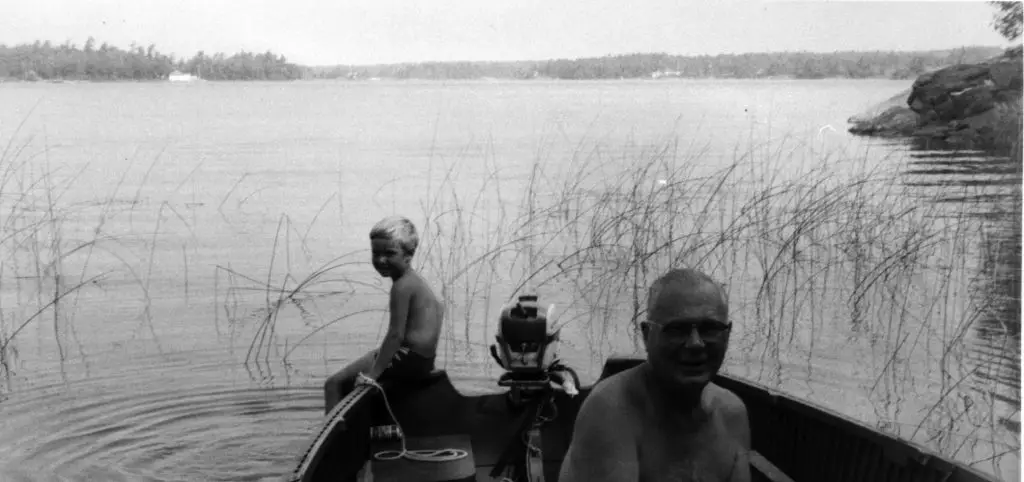

One thing about being a child is that regardless of your situation, you always regard it as normal – at least until you get older. And that’s why I grew up thinking that all grandfathers had white beards, spent weeks and weeks fishing with their grandsons every summer, gave them really great birthday gifts, and taught the noblest life lessons by example. Now that I’m a grandfather myself (11 years in at this time), I find myself thinking of my granddad more than ever – thinking about the legacy he left behind and how I’d like to live up to it.

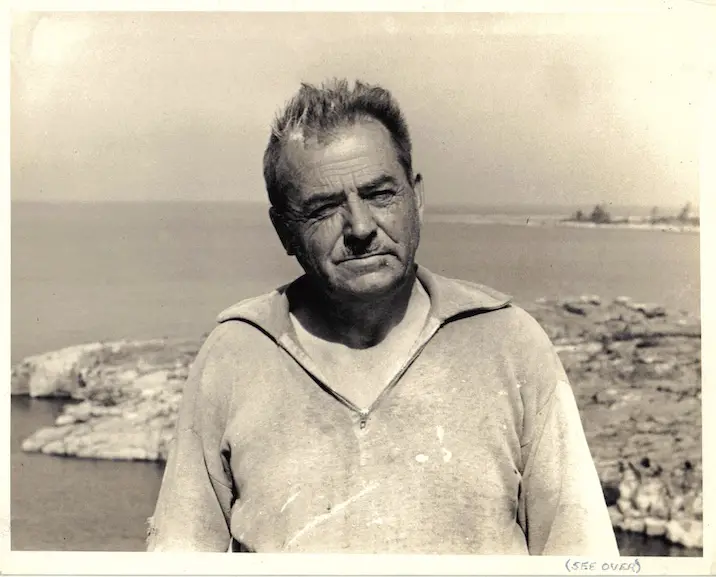

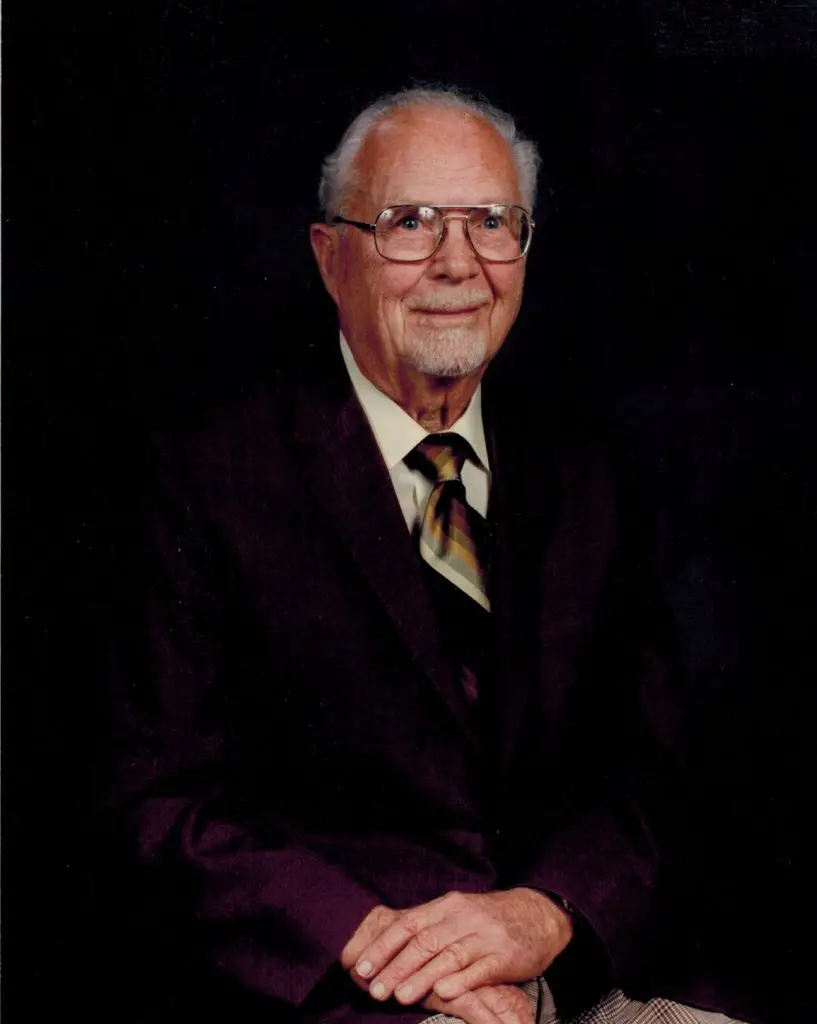

Kenneth Robert Maxwell (everyone called him Ken) was a career employee of the Goodyear tire company, and a true gentleman. He died on September 1, 1995 and this still brings tears to my eyes. Grandpa (that’s all I ever called him) was born on August 26, 1907 in Port Credit, Ontario, Canada. Grandpa’s father, Robert Maxwell, was an English-trained cabinetmaker who spent his entire working life as head carpenter at the mental hospital on Lakeshore Avenue in Toronto, not far from the Goodyear tire plant in Etobicoke where Grandpa would work one day. I’ve often wished I could travel back in time to when Grandpa was a boy playing on the beautiful lakeside grounds of that hospital.

When you think about mental hospitals, the images aren’t pretty. But back then, at least at this place, they did things differently. I know because Grandpa took me to see the grounds one day when I was in my 20s. The hospital had been shut down for years, but the buildings were still there. We snuck through the abandon buildings together, just before the property was slated for redevelopment into condos or something modern.

“Over there were the vegetable gardens where the patients grew their own food”, he pointed out. “And that building was the main workshop where your great grandfather, my dad, worked”. I wonder if Grandpa and I would become friends as 10 year-olds riding together on food carts we’d race through the underground tunnels leading from one hospital building to another. Grandpa often told stories of how the apples that grew on the property got so much sweeter after the first few fall frosts. Every autumn as a boy he’d sneak some out of the holes in the ground they put the apples in to keep them over the winter. All this set alongside the shimmering waters of Lake Ontario in a by-gone era.

I was always interested in those parts of Grandpa’s life that came before I did, so I asked him many questions over the years. And since he spent almost his entire working career at Goodyear, many of the answers he gave had to do with that company. During the years before and during World War II, for instance, he was transferred to the Winnipeg operation where he sold truck tires. That’s where he met the woman who’d become my grandmother, Anne Grant. My Dad was also born in Winnipeg in 1940, their first and only child. They named him Wayne after the famous dance band leader of the time, Wayne King.

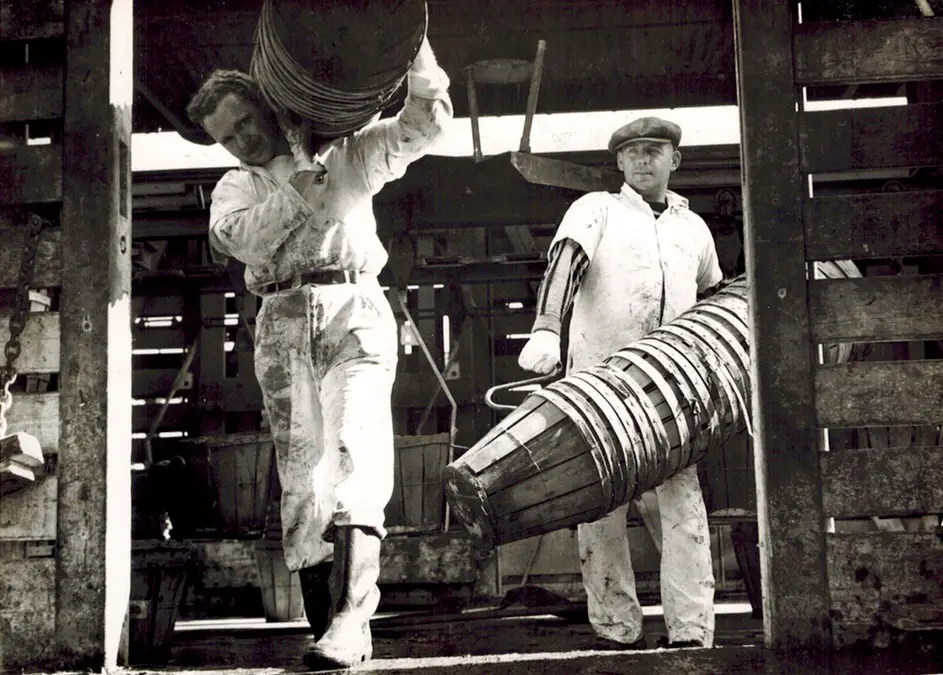

The attending doctor at my Dad’s birth turned out to be drunk at the time, leading to injuries to my grandmother that prevented my grandparents from having any more children. The medical expenses threw Grandpa deeply into debt for decades. Grandma worked full time for her whole life helping to cover the costs of those medical debts. She died early, when she was only 50. Grandpa took on a second job in a soup factory to help cancel the debt. That’s him below on the left on a weekend shift handling tomatoes.

I grew up hearing lots of stories about how bad life was during the depression, but Goodyear was a powerful cushion against that for Grandpa. When I asked him what life was like during the dirty thirties, I expected grim stories. But as it turned out, the only financial hardship he had to endure at his job was a 10% pay cut.

Grandpa and Grandma moved back to Ontario shortly after my Dad was born, and Grandma died in 1967. Though I was only four years old at the time, I do remember her clearly. That’s easy since my Mom and Dad and I lived with Grandpa and Grandma in the crudely finished basement of their tiny, post-war bungalow in Etobicoke, Canada during my earliest years. I still remember being allowed to jump on their bed as much as I liked (something my parents never let me do on their bed), and yelling the words Good-Good-Goodyear! at the top of my lungs as I did. That same basement, unchanged from when I was there as a boy, is the place where my wife and I lived for the first few years we were married in the late 1980s, with good old Grandpa still upstairs.

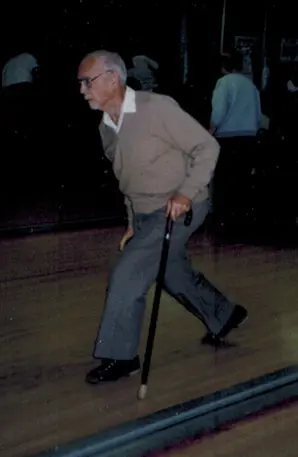

There are important things from Grandpa’s life that are firmly rooted in me to this day, things he taught by example. Perhaps you’ll find them useful in your own life. Grandpa was always kind that I saw and he endured every discomfort without complaining. “Long suffering” they called it years past, though out of fashion now. As a younger man he was a master bowler, scoring a number perfect games – every ball knocking down every pin, every time. But even when he had to use a cane in later life, Grandpa never gave up on the game. I never heard any kind of foul word leave his lips, not even once and not even when he was well within his rights to say them. He had a clean heart and great endurance. One Sunday afternoon, for instance, he took me skating on a local pond when I was about 7 years old. In saving me from a fall, he went down on the ice himself and landed hard on his left arm. We finished our skating session and went back to my house for roast beef dinner – our usual Sunday afternoon pastime with him. His arm obviously hurt during the meal, though he stayed as long into the evening as usual. We found out the next day that he had broken his arm in the fall, driving 30 miles back home the night before. I still remember the words he offered when I told him how badly I felt: “Don’t worry, Steve. It’s just pain.”

As I grew up, Grandpa introduced me to many things that have since fallen out of the usual areas of grandfatherly expertise. He taught me how to shoot a .22 rifle, he showed me the way to use patience and a Swede saw to cut a pile of firewood without getting discouraged at the size of the task. He also taught me the value of saving money a little at a time.

I get sad when I think that I can’t pick up the phone and call Grandpa anymore. It’s been 28 years since I could do that. I will always miss him, at least during my time on this side of eternity. But that’s balanced by the gratitude I feel for the time we spent together. Ken Maxwell was a good man. It’s one of my treasured blessings that I call him Grandpa. His legacy shines in a world where the qualities of selflessness, hard work, frugality, good humour and kindness seem to be in short supply and dwindling. And isn’t that something that all of us might be a little better off remembering, whether we’re a grandfather or not?