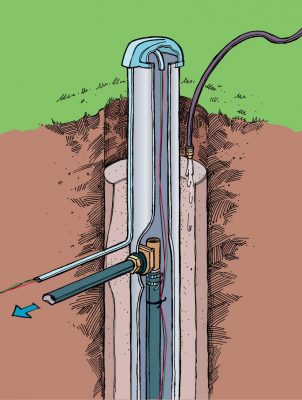

Wells can be deep or shallow, drilled, dug, bored or driven. Drilled wells are typically small in diameter (4 to 8 inches), more than 25 feet deep and are the only option for accessing water from bedrock. Drilled wells like the one you see here include a metal tube (called a “casing”) pushed into the hole in the ground far enough to extend down past any soil that might be present, then further on into bedrock. Casings also extend several feet above the surface to keep out surface water and dirt. Even when you need to drill 100 feet or more through bedrock to get water, modern drill rigs do the job in a day or less. My own drilled well is 143 feet deep, with the first 6 feet going through soil. The rest is limestone bedrock.

Wells can be deep or shallow, drilled, dug, bored or driven. Drilled wells are typically small in diameter (4 to 8 inches), more than 25 feet deep and are the only option for accessing water from bedrock. Drilled wells like the one you see here include a metal tube (called a “casing”) pushed into the hole in the ground far enough to extend down past any soil that might be present, then further on into bedrock. Casings also extend several feet above the surface to keep out surface water and dirt. Even when you need to drill 100 feet or more through bedrock to get water, modern drill rigs do the job in a day or less. My own drilled well is 143 feet deep, with the first 6 feet going through soil. The rest is limestone bedrock.

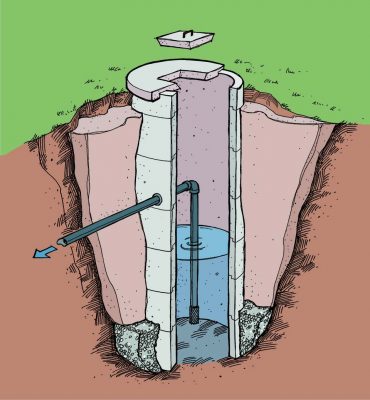

Dug wells are just as the name sounds. They’re holes dug into the soil only (no bedrock) to a relatively shallow depth. Traditionally, dug wells were shoveled out by hand and lined with stones, but today they’re usually created with a backhoe or excavator. Dug wells can be created only in soil of some kind, they’re typically 24” to 36” in diameter, and usually less than 20 feet deep. These days tubular concrete well tiles keep soil and surface water out of the hole, instead of hand-laid stonework.

Dug wells are just as the name sounds. They’re holes dug into the soil only (no bedrock) to a relatively shallow depth. Traditionally, dug wells were shoveled out by hand and lined with stones, but today they’re usually created with a backhoe or excavator. Dug wells can be created only in soil of some kind, they’re typically 24” to 36” in diameter, and usually less than 20 feet deep. These days tubular concrete well tiles keep soil and surface water out of the hole, instead of hand-laid stonework.

Bored wells are another option. They’re just like the dug well you see here in the illustration, except deeper. Created by specialized equipment that augers a round hole in soil only, this lets bored wells go deeper than dug wells (up to 50 feet deep). The boring operation is less disruptive to the surrounding landscape than using a backhoe or excavator, too. Bored wells also use concrete well tiles to keep surface water, dirt and critters out of the hole.

Driven wells are completely different than anything else. They’re made by fitting a sharp, rigid, screened attachment that threads onto the end of rigid steel pipe. This attachment is called a sand point, and it allows a pipe to be pounded into the ground using a sledge hammer or jack hammer for extracting groundwater from abundant, relatively shallow sources in coarse soils. Sand points are the simplest and cheapest option for getting a well, but they only work in sandy or gravelly soils with water close to the surface.

Driven wells are completely different than anything else. They’re made by fitting a sharp, rigid, screened attachment that threads onto the end of rigid steel pipe. This attachment is called a sand point, and it allows a pipe to be pounded into the ground using a sledge hammer or jack hammer for extracting groundwater from abundant, relatively shallow sources in coarse soils. Sand points are the simplest and cheapest option for getting a well, but they only work in sandy or gravelly soils with water close to the surface.

Water Wells at a Glance

How can you quickly tell what kind of well you have? Check out these telltale visual features and you’ll know.

Drilled well: The only kind of well with a metal casing that extends above the ground. All drilled wells have (or should have) some kind of metal cap on top of the casing.

Hand-dug well: This could have a wood or metal cover, usually flush with the ground. If you see round field stones lining the insides of the well when you look down into it, you’ve got an old-time dug well. Just imagine what it would have been like to dig one of these.

Modern dug well: If you see a round concrete cylinder and cap about 3 feet in diameter and extending above the ground, you may have a modern dug well. If total well depth is less than 20 feet, it is dug for sure (not bored). Your well was created by a backhoe or excavator, with the concrete tiles installed one on top of the other, then the soil replaced.

Bored well: This will have the same kind of concrete cap of a dug well, but it’ll be deeper than about 20 feet.

Sand point: If all you see coming out of the ground is a metal pipe a couple inches in diameter, then you’ve got a sand point. A sand point well isn’t as common as other types of wells because it takes uncommon geological conditions to support one. You need sandy or gravelly soil with a water table that’s less than 20 feet from the surface. In regions with winter temperatures that go down below freezing, the entire pipe could be buried, or it could end in a pit below the frost line with an access cover.

Watch the video below about a water well being drilled in the limestone bedrock of the Canadian island where I live. This well has since proven to be very productive with a flow rate of about 50 gallons of water a minute.